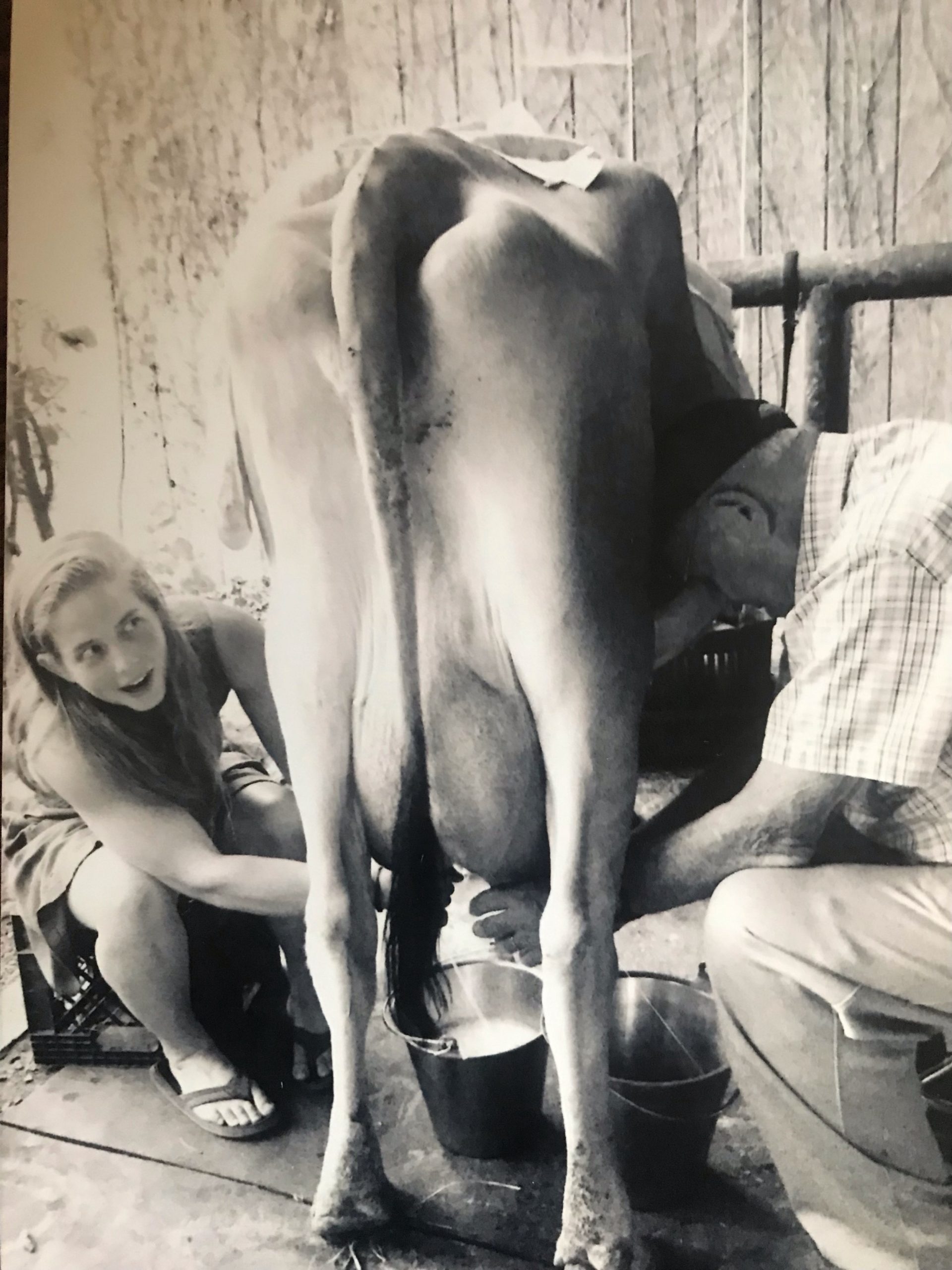

This week’s Easter celebration involved Sunday brunch and farm walks, then an afternoon family dinner featuring my 97-year-old father, Joe Muller (in the picture above) and lots of stories of life in Switzerland in the 1930’s and 40’s, and of the journey to the states after the war to a life of farming in a wildly open and abundant California.

Ask him a question and the memories and stories are clearly recalled: walking cows into the Alps from his home in Altdorf, a journey of more than 20 miles made each spring when snow cleared and the grass turned verdant and lush, his first potato crop as a teenager, and great tales of the mischievous pranks that he and his brothers were well known for in their small Swiss town.

In those springs and summers high in the mountains, he made cheese each day with his brother Carl. From the age of 12, he milked 15 cows by hand twice a day, then heated, curdled and finished cheese rounds in a cellar dug into the mountainside. A summer of work yielded heavy cheeses that were loaded up in the fall as they walked the cows down the mountain. He recalls his pipe-smoking aunt Yohanne with a gait that he had to near run match and her ability to hike up the alp as if the mountain wasn’t steep or tiring. Together they drove cows up the alp in the spring and then returned to take them down four or five months later in fall.

As one of 9 children, he gathered his resources, left Altdorf and came to California after World War II ended. He left a time and history where he said his poor grandfather was indentured to a farmer, working a full year for one shoe, and the next year for the other shoe. He recalls that those days making cheese high in the mountains were some of the loneliest of his life. Yet, he became a dairyman here.

But America was different; opportunities were abundant and he started milking cows on a dairy in the Los Angeles area. There he tended cows for more than 16 hours each day, and nearly worked himself to sickness. The doctor mandated time away from cows and he spent three years as a logger in the Northern Redwoods. He often expresses regret for those years when his job was to fell and harvest some of the world’s most magnificent trees. His work ethic was relentless and his love of cows enduring, so he returned to the dairy world and started his own- meeting my mother Marie who he asked to milk cows and be his partner.

They were quite a team- building a drive-in-dairy business, milking 250 head, bottling milk, cream and all types of dairy products, dancing to Swiss Polkas on the weekends and having six children. We all grew up working at the dairy and falling in love with the freedom, the creativity from ones own work, and the tangible accomplishments made each day. All six children ended up as farmers- my trajectory was to leave the fold of ‘regular’ farmers and start and organic farm with Dru in 1982.

Cows are remarkable in their near universal gift of rich creamy milk and all that can be made from that product. Dru has milked a home cow here on the farm for 34 years, and now Becca milks two that produce 10 gallons each day. We are kept flush in milk, cream, yogurt, and even ice cream here by this gentle relationship with these beautiful animals. My dad still recalls this lifelong friendship and affinity for cows- the care he promised and their generous gifts given each day. He pastured his animals and made all of their winter feed each summer in a great model of responsible stewardship.

I visited Rwanda this past summer where a program there is making sure that each child in the country was given a glass of milk each day to help alleviate hunger and that under a program called Grinka, more than 250,000 cows have been given to poor families that meet the following qualifications:

Beneficiaries must not already own a cow, must have constructed a cow shed, have at least 0.25–0.75 hectares of land (some of which must be planted with fodder), be considered poor and an Inyangamugayo (person of integrity) by the community and have no other source of income. Beneficiaries who do not have enough land individually may join with others in the community to build a common cow shed (ibikumba) for their cows. Priority is given to female-headed households.

Cows are often vilified for their impact on the planet, but for these families, they bring a tremendous benefit.

But how did I get to cows? One thought leads on to another, and the Beet soon becomes a ramble of associations. My father’s lifetime includes some of the most remarkable years that one human might experience. From walking cows in the Swiss mountains to a wide-open California where in the late 1940’s (and beyond) the opportunities have been remarkable, the resources seemed limitless and abundant, and the common post-war determination and work ethic was infectious. Bring that life history to today, witnessing the power of media, and computing—for him, the changes have been mind-boggling.

Those experiences are best related as stories- snapshots of different times shared over a meal in spring. Spring, and this weekend’s rain, make promise and possibility seem a resurrection and renewal of hope and trust in universal connections with nature (leafing trees; wild enthusiasm of bees, insect life, and singing birds; milk and cows; and bursts of delicate intricate blooms…). Stories from a 97 year old remind us of our own story making and the creative possibilities and truths gleaned from a generous land.

The food we share is more than a meal. It is the window into nature and the bounty of the land, the story of the love of carefully tended animals, and the story of the history of your farmers. Looking at our small farm this Easter shows a place, that when stewarded with love, makes good food for you, becomes its own evolving tale for me, and makes chance to share your meal and story with your kin. The meal becomes a moment to give thanks for the grace and blessings that make each day rich and rewarding and for all that will be here long after we pass.

Yesterday on our walk, we marveled in seeing so many different bees dancing in our flower fields; the amount of wildlife feasting on the purple vetches and red clovers; and the iridescent hummingbirds flashing green and then ruby red.

In my father’s 97 years, the constructed world has changed a great deal. Yet there are things that remain part of our very being –our need for stories to connect us to each other; the abundant expression of life gathers at the table that is set with good intention and restraint; the wild edge, when fed, shows up to share with us a time of renewal and hope. The cows here have coats slick and glistening with good grass and then most happily share their rich milk with us…. As it has been, so it shall remain… Happy Springtime!

-Paul Muller