After four weeks off, over seven inches of rain, finally a bit of sun after weeks of fog, and some much needed time off, we’re back from our winter break and ready to get back to farming! Welcome back to returning CSA members, and welcome to the many new folks joining our community.

There are many reasons to join a CSA but one key reason is a close connection to your food and knowing where it comes from, who grows it, and how it was grown. The other is enjoying tasty, fresh, nutritious produce. Our main way of helping you with these goals is via our newsletter, the Beet. You can sign up to get the Beet sent to you every Monday – there’s a link at the bottom of the home page. The Beet tells you what the Tuesday CSA members are getting, provides recipe ideas and storage tips, and has the “News from the Farm” section with notes and photos about what we’re up to. Plus other announcements. We also have a website with hundreds of recipes categorized by produce type, plus over 14 years of farm news to peruse.

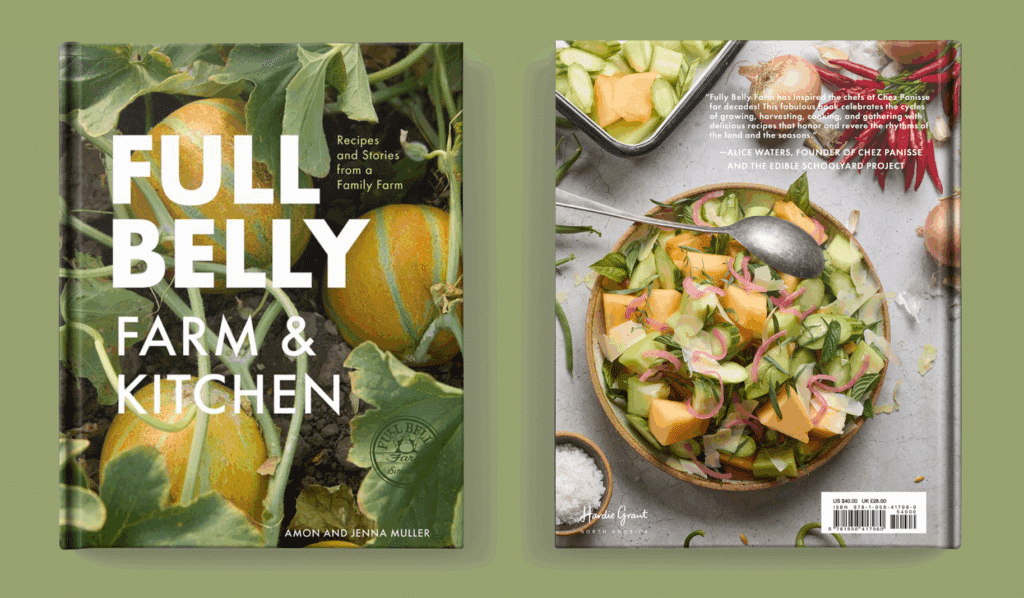

But we’ve been farming for longer than that! Full Belly Farm was started in 1984 and certified organic in 1985. That’s over forty years of organic farming! We’re also certified by the Real Organic Project (more about that here).

We’re located on about 350 acres in the stunningly beautiful Capay Valley, between Guinda and Rumsey (map here). For reference, one acre is almost one football field, 16 tennis courts, or nine basketball courts. We’d love for you to come up and visit during one of our many events: our annual spring CSA Day, one of our summer monthly Friday night Pizza Nights, a Farm Dinner, or one of our other special events. We’ll be announcing Farm Dinner dates within the next month or so, and CSA members and Beet readers hear about them first, so always make sure to read the Beet!

We’re an incredibly diverse farm. We’re growing hundreds of varieties of vegetables, fruits, and flowers, plus nuts (almonds and walnuts), grains (wheat, barley, and corn), and oil crops (olives and safflower). We also raise sheep, chickens, cows, and pigs and sell eggs, meat (seasonally), yarn, and sheepskins. We have a certified kitchen where we dry fruit and make jam, baked goods, and more. All items from the kitchen are made with produce (or flour) that we grow and all items can be added to your CSA boxes! We recommend that you peruse the web store from time to time, but we also send out emails about extra items.

How do we manage this incredible diversity? It starts with good leadership! We have seven owners (from left to right in the photo below): Amon Muller, Jenna Muller, Paul Muller, Dru Rivers, Hannah Muller, Andrew Brait, and Rye Muller. Each has their own area of the business that they’re in charge of. It’s a true (multigenerational) family farm: Amon, Hannah, and Rye are Dru and Paul’s children, and Jenna is Amon’s wife.

Photo Credit: Ella Gallaty

In addition, we’ve got about 65 year-round employees (see the photo of us on top) plus more folks who join us during the summer. Some of my coworkers have been working here for 30+ years! Everything is a true team effort and everything you get reflects the hard and careful work of countless people from seed to delivery, and the many steps in between.

In addition to our CSA, we attend three farmers markets each week (the Tuesday Berkeley Farmers Market, Thursday Marin Civic Center Market, and Saturday Palo Alto Market), we sell to small grocery stores plus bakeries and restaurants, primarily in the San Francisco Bay area and Sacramento/Davis areas, and sell to a couple large wholesalers.

That just scratches the surface, but it addresses some of the most common questions we’re asked. What are some questions that you have about our farm? Let me know and I can answer it in an upcoming Beet.

A few reminders:

ALWAYS check the sign-out sheet before you take a box, flowers, or anything else. Don’t take anything that isn’t listed with your name. It’s frustrating and disappointing when someone arrives to find out that their items aren’t there. If your name isn’t on the list, reach out to me in the office (email or phone) and we’ll figure it out.

Everyone has the ability to skip or donate a box if they’re going to be gone. The cutoff to let us know is two full days before your delivery date (i.e. Saturday night cutoff for a Tuesday box). Skipping or donating via the CSA website is easy to do, or you can email. Skipped boxes are moved to the end of your schedule, unless you request otherwise.

If you can, consider donating a box instead of skipping. Thanks to CSA member generosity, last year we donated five boxes each week to the Charlotte Maxwell Clinic and subsidized $5,000 of CSA payments for your fellow CSA members.

Lastly, don’t be a stranger! If you have feedback (positive or “constructive”), a recipe to share, or a question for us, please reach out! We believe very strongly in the Community part of Community Supported Agriculture and want this exchange to be more than a transactional money-for-produce exchange. We’re real people, growing real food, and we appreciate the relationship we have with all of you.

Elaine Swiedler, CSA Manager